At the end of the pages of the Shema, on page 158 in Siddur Lev Shalem, we call out to God - usually in full-throated deep voice - requesting that God, our “Rock” or “Stronghold,” arise and help us, and redeem Judah and the people Israel as promised. We then refer to God as our “Redeemer called Adonai Tzeva’ot (of Armies).”

And then we revert to the past tense, falling off into a softer musical tone, and offer a berakhah saying, “Barukh atah Adonai, who liberated the people Israel.” If only the leader is chanting, we do not break the flow from the Shema to the Amidah by adding “Barukh Hu uvarukh Shemo,” but we do (we must) say “Amen.” And then we fall to silence with the Amidah. (“Amen” after a berakhah is always required when someone else is saying the berakhah.)

Our siddur and other sources tell us that this last blessing links the recitation of the Shema to the personal prayers of the Amidah, and thus we should not speak any extraneous words between “Mi khamokhah” and the Amidah. The siddur mentions that “it is as if to say that the possibility of prayer flows out of our experience of God’s love as exhibited in freeing us from slavery.” According to Or Hadash by Reuven Hammer (commentary on Siddur Sim Shalom), based on interpretation of Talmud (Berakhot 9b) they started a custom that the leader say the berakhah quietly and there was no “Amen.” That continues in some congregations.

However, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly at some point determined that the leader should recite it aloud and that there should be an “Amen.” So it is done various ways: some congregations recite the berakhah with the leader, thus obviating “Amen”; some congregations even begin the Amidah during the berakhah so they do not say “Amen.”

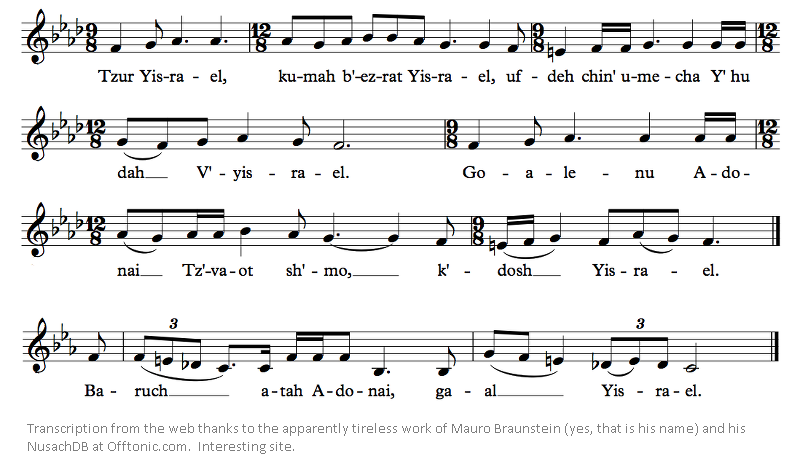

So the musical segue seems intentional. The tune, by the way - the Nusah - is in the freygish mode, which is also known as the “Ahavah Rabbah mode,” in non-Jewish terms the Mixolydian mode of a melodic minor, or a form of the Phrygian mode, depending on the tune.